Practices of (Re)Commoning at the Industrial Heritage Site Cerro Rico and Mining Tourism in Potosí, Bolivia

Cerro Rico, a mountain nearly 4,800 meters high, is known as the world’s largest silver deposit and located next to the city of Potosí in southeastern Bolivia. It is perceived in two distinct ways: on the one hand, as a site of historical and cultural heritage, and on the other, as one of ongoing industrial activity. Within this context, the predominantly Indigenous miners working inside Cerro Rico strive to resist Western appropriation. Mining tourism plays a crucial role in this process.

In the following, I will discuss the processes of uncommoning and recommoning surrounding the activities at the heritage site Cerro Rico. By “uncommoning,” I mean the process through which something shared, an object, a space, or a practice, is taken away from a community and turned into something controlled by external actors, such as colonial powers, private entrepreneurs, or state institutions. “Recommoning” refers to attempts to reclaim or re-embed this shared good within community life.

Fig. 1. Miners inside Cerro Rico. Schacht 2024.

Mining in Potosí in colonial times and today

Silver was already being extracted in the region around Potosí during pre-colonial times (Cruz and Absi 2008). Although archaeologists disagree on whether this included Cerro Rico itself, it is widely assumed that Inca and pre-Inca populations were already aware of the silver deposits (Absi 2005). What is certain, however, is that Cerro Rico served as a huaca, a sacred site, and played an important religious role for the Indigenous people in the region (Lane 2019). The impressive, cone-shaped Cerro Rico was revered as sumaj orqo, meaning “beautiful mountain” in Quechua.

From 1545 onward, when the Spaniards learned of the silver deposits in Cerro Rico, Potosí developed into the center of colonial silver production and extractivist economy. In this process, the Indigenous population was dispossessed of their sacred mountain, which was transformed into an industrial site. This marked the first process of uncommoning at Cerro Rico. By the 17th century, half of the world’s circulating silver is said to have come from Potosí (Lane 2019), which was only made possible through the massive exploitation of Indigenous forced laborers and African slaves. Profits, however, went primarily into European hands (Bakewell 2010, 227-230).

Already in the 17th century, a first subversive attempt at recommoning was carried out by Indigenous kajchas who secretly extracted minerals in Spanish mines, often keeping the most valuable for their own. This practice of kajcheo continued even after Bolivia’s independence, particularly in the early 20th century. By then the mines were focused primarily on the extraction of tin and were controlled by wealthy entrepreneurs. With the Bolivian Revolution of 1952, a form of recommoning of the mines took place through the nationalization of all mines, paving the way for the emergence of cooperatives inspired by the kajcheo tradition during the 1980s and 1990s (Absi 2005).

Today, mining at Cerro Rico remains active, and is mainly organized through these cooperatives. Working conditions have changed little since colonial times and are still extremely dangerous and detrimental to the miners’ health (Francescone and Díaz 2013, 39-40). Most miners are nowadays Quechua-speaking Indigenous men whose ancestors often worked in the mines for generations, in some cases dating back to colonial times (Pretes 2002, 440). Although many take pride in their work, they are stigmatized by large parts of Bolivian society and receive little attention or social recognition (Absi 2005). Around 12,000 miners work in 32 cooperatives at Cerro Rico, and mining continues to be the most important economic activity in Potosí (Flores 2024).

Fig. 2. View of the Cerro Rico from the center of Potosí. Schacht 2024.

Potosí and Cerro Rico as historical heritage

In 1987, Potosí was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In particular, emphasis has been placed on the city’s historical relevance, as its silver deposits substantially contributed to the development of the global capitalist system. The heritage site “City of Potosí” includes parts of the colonial infrastructure for silver production within Cerro Rico, the historic center of Potosí, and the “Casa de la Moneda”, the royal mint (UNESCO 2025).

From official sides, a specific heritage discourse has emerged around Potosí. The focus lies on the colonial architecture of the city center and particularly on the “Casa de la Moneda”, today one of Bolivia’s most important museums. Within the highly professionalized and institutionalized “Casa de la Moneda”, colonial history is presented from the viewpoint of the colonizers. The colonial period is romanticized and trivialized for national and international tourists, thereby reproducing Eurocentric perspectives and colonialist narratives. For instance, during guided tours of the museum, pre-colonial mining is not mentioned at all, and Indigenous forced labor and African slaves are only mentioned briefly. Instead, the wealth of colonial Potosí is repeatedly emphasized, and the colonial period is portrayed in a positive light.

Overall, Potosí’s World Heritage status is justified through its colonial history, while pre-colonial pasts or current mining activities are largely excluded. This can be understood as a hegemonic historical discourse in which alternative or Indigenous perspectives are distorted or silenced, a process that can be interpreted as a form of uncommoning. Within the official heritage narratives, Cerro Rico is reduced merely to a scenic backdrop and the mining itself is largely ignored. Yet it is precisely this backdrop that plays a crucial role in the patrimonialization of Potosí, something that has become particularly evident since 2014.

In that year, UNESCO placed Potosí on its “List of World Heritage in Danger” due to the risk of collapse of Cerro Rico, caused by ongoing mining activities (UNESCO 2014). The mountain is now crisscrossed by an extensive system of tunnels and shafts, with a total length of over a thousand kilometers (Quintana C. 1998, 21). The continuous extraction of minerals over time has rendered many areas highly unstable.

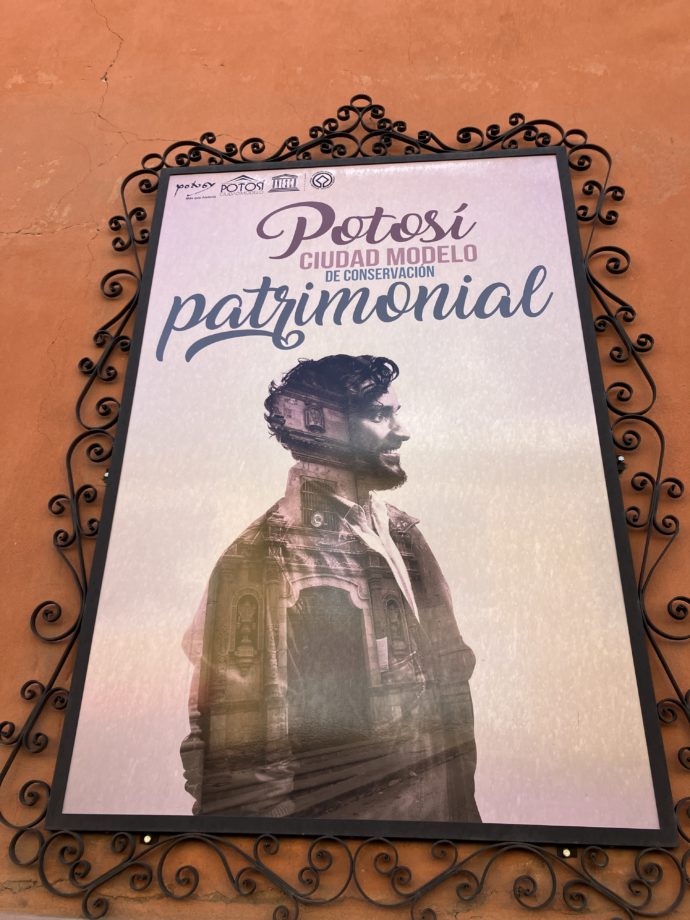

Fig. 3. Poster in the historic center of Potosí. Schacht 2024.

Historical heritage site or active industrial site?

Since the late 1970s, Bolivia has experienced an intensified process of patrimonialization, which has at times been strongly politicized. General critiques emphasize that these processes largely reflect elite discourses and neglect marginalized perspectives (Absi and Cruz 2005). More specifically, there is an ongoing controversy over the patrimonialization of Potosí and Cerro Rico. In this context, the industrial dimension of Cerro Rico is often disregarded, as the mountain is framed primarily as a historical heritage site of the past.

The resulting conflict lies in the fact that the continued industrial use of the mountain by miners stands in direct opposition to its patrimonialization. UNESCO’s approach represents a static and preservation-oriented conception of heritage. Many miners, however, view themselves as custodians of a living industrial heritage that cannot be confined to the past (Absi and Cruz 2005). Mining is inextricably intertwined with the history, present and probably even the future of Cerro Rico (Quintana C. 1998).

Industrial heritage is closely linked to local identities (Xie 2015). Some actors argue that Potosí’s designation as a World Heritage Site has strengthened the city’s and its habitants’ self-esteem, allowing the heavy burden of history to be reinterpreted in a more positive light. Cerro Rico, as industrial heritage site, plays a particularly important role in the local identity of many miners and residents of Potosí. Nevertheless, as I observed during my own ethnographic field research, many residents express criticism of the Eurocentric logic underlying UNESCO’s concept of heritage and of the state institutions that reproduce this discourse.

Above all, miners criticize the designation as World Heritage Site and its consequences for their work. Many argue that by defining the unchanged preservation of Cerro Rico as its primary goal and blaming miners for its “destruction,” UNESCO fails to acknowledge that mineral extraction has always been integral to Potosí, and that the site’s heritage value is rooted precisely in this ongoing practice (Absi and Cruz 2005). This creates an opposition between the “good” who “protect” the heritage in accordance with UNESCO’s criteria, and the “bad,” who do not acknowledge it and are thus criminalized (Gnecco 2019). Moreover, the official heritage discourse ignores the fact that it is the miners themselves who maintain the infrastructures in the Cerro Rico declared as World Heritage, precisely because they continue to use them.

Miners perceive the patrimonialization as a form of uncommoning of their active industrial heritage site, which thus becomes a historical heritage site as defined by UNESCO and other institutions. Yet miners contest the official patrimonial narrative and reclaim agency over how Cerro Rico is represented. They use own forms of mining tourism to counter Eurocentric heritage views.

Mining tourism in Potosí

Mining tourism is a topic that has so far received little scholarly attention, particularly from an ethnographic perspective. Yet the encounters that take place within this form of tourism actually represent a very good subject for qualitative empirical research at the micro level.

For my bachelor’s thesis (Schacht 2024) I conducted three months of ethnographic field research and focused on mining tourism in Potosí. I conducted participant observations using different approaches during several guided tours in five different mines. In addition, I carried out participant observations during guided tours of the “Casa de la Moneda” and other sites of tourist infrastructure, including the city center, souvenir shops, travel agencies, and a training center for tour guides. I also conducted several semi-structured interviews and informal conversations with miners, international tourists, tour guides and institutional actors such as the tourism police, staff of the tourism information office, and instructors at the training center for tour guides.

I argue that mining tourism can be a form of recommoning industrial heritage sites but that Eurocentric perspectives on this type of tourism pose a problem in this context.

Fig. 4. Group of tourists and their guide at the mine entrance. Schacht 2024.

Mining tourism as a recommoning process

Since the mid-1980s, guided tourist tours have been offered in the active mines of Cerro Rico. Initially informal and improvised, these tours have gradually become more professionalized. Today, agreements exist with certain mines regarding visitor access, including fixed entry fees. It is important to note that these tours were initiated and organized by the miners themselves, motivated by a desire to share their impressions and experiences (Pretes 2002). Even today, tour guides are almost exclusively former miners or their children. Many continue to see themselves as part of the mining community and maintain a strong sense of solidarity with current miners.

Beside guided tours, in some cases, miners also created small museums inside the Cerro Rico for tourists. However, these museums no longer exist today, as those spaces have since been returned to active mineral extraction.

In contrast to other heritage tourism sites in Potosí, such as the “Casa de la Moneda,” mining tours are guided by miners themselves, allowing them to convey their own perspectives, including those of colonized and marginalized subjects. This form of tourism can therefore be understood as a process of recommoning the industrial heritage of Cerro Rico by the miners and their community. Through the mining tours, miners can disseminate an alternative, or at least a broader, narrative that challenges the official colonial-historical and heritage discourse. This alternative narrative does not glorify or trivialize the colonial period, as happens for instance in the “Casa de la Moneda.” Instead, it addresses the working reality of miners, their religious beliefs, the dark sides of colonial history, pre-colonial mining, the organization of cooperatives, and personal autobiographical experiences and stories. Guided tours by miners thus present broad insights and knowledge informed by their daily work in the mines.

The mining tours primarily focus on the miners’ current work. In doing so, they reinforce the perception of Potosí as an active industrial site rather than merely a historical one. The guides are also keen to encourage dialogue and direct exchange between tourists and miners, acting mostly as translators while allowing the miners themselves to speak. For many guides, the main motivation is to generate recognition and respect for the miners’ labor.

Fig. 5. During a tour at the shrine of the Tío. Schacht 2024.

Eurocentric critiques on mining tourism

Mining tourism allows miners to present their own perspectives and to challenge dominant narratives about Cerro Rico. However, this potential for dialogue is rarely realized in practice, as many visitors, shaped by Eurocentric perceptions, interpret the miners’ agency and self-presentation primarily through the lens of suffering.

Tourists play an active role in the meaning-making processes of heritage sites (Smith 2021), and both – their perceptions and the Eurocentric frameworks shaping them – warrant careful analysis. During my research, I observed that many tourists, mostly coming from Europe and North America, experienced ethical discomfort and a sense of guilt while visiting the mines. This is mainly due to a feeling of “voyeurism.” In her well-known essay Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), Susan Sontag noted that the desire to observe the hardships of others affects many people. Yet, at the same time, people reject and condemn this very desire (Vergopoulos 2016, §43).

This feeling was expressed by one tourist I interviewed after visiting the mine:

I didn’t feel great, kind of being in their space like that. In a way that was like „Oh, we just come here to look at you suffering and leave.” […] It’s basically „We are here to see what kind of suffering you go through and then leave and go back to our comfort.” […] I mean I paid a tour company to take me there, like it’s… It doesn’t feel great. (Personal communication, March 1, 2024)

Although this criticism may appear well-considered and self-reflective at first glance, a closer examination reveals that the very feeling of voyeurism is itself a product of Eurocentrism – a reproduction of colonial thought patterns rooted in the failure to genuinely listen to the miners’ own voices.

My research indicates that many tourists hold a paternalistic view of the miners and their labor. As Rivera Cusicanqui (2010, 24-25) and Macusaya Cruz (2020, 40-41) argue, the perception of labor as “suffering” or “misery” stems from a Eurocentric conception of work that, since colonial times, has devalued physical labor and denied it dignity. Yet many miners take pride in their work, viewing it as a source of identity and even, at times, of pleasure. The paternalistic compassion expressed by many tourists can be understood as “affective side of coloniality” (Castro Varela and Heinemann 2016, 56, transl. Schacht).

A meaningful and decolonial critique of mining tourism can only emerge through dialogue with the miners themselves (Rivera Cusicanqui 2010). Even though mining tourism holds the potential to foster such dialogue, Eurocentric perspectives and paternalistic attitudes often prevent it. My research showed that many miners hold a rather positive view of mining tourism. However, only a few tourists perceive this, as the majority fails to truly listen. By ignoring the miners’ perspectives and focusing instead on power inequalities, the tourists not only perpetuate these inequalities but also construct the miners as subaltern subjects who “cannot speak” and are thus excluded from political subjecthood (Spivak 1988). Such inequalities undoubtedly exist on a structural and systemic level, but on the micro level, within the concrete setting of the mining tour, the miners clearly occupy a position of authority, as the tourists depend on them.

Discourses that interpret tourism primarily as an imperial exercise of power fail to recognize the agency demonstrated by the miners and reduce them to a victim role they do not identify with. Through mining tourism, the miners actively assert their agency and “speak” for themselves. Yet their voices often remain unheard by many tourists, paradoxically due to their feeling of guilt. This lack of listening as a Eurocentric consequence is precisely the problem: the miners’ efforts to recommon Cerro Rico through tourism often go unacknowledged and misunderstood, limiting their impact on many visitors.

Conclusion

Throughout the history of Potosí and its mining activities, various processes of uncommoning and recommoning can be identified. The designation of Potosí as a UNESCO World Heritage Site marks the starting point for an ongoing debate over whether Cerro Rico should be understood primarily as a historical heritage site or as a living site of industrial activity. Within this context, mining tourism can be seen as an attempt by the miners to recommon Cerro Rico. Yet Eurocentric perspectives among tourists often interfere with this process by reproducing colonial hierarchies and patterns of thought.

The recommoning of Cerro Rico through tourism constitutes an important step toward reclaiming agency and redefining heritage from the miners’ perspectives. However, this effort must go hand in hand with dismantling colonial structures and discourses. Ultimately, mining tourism in Potosí reveals both the potential and the limitations of recommoning processes under global heritage regimes.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks all those who contributed to this research, especially the interview participants and the miners at Cerro Rico. He also thanks Ingo Rohrer and Antje Gunsenheimer for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this text.

References

Absi, Pascale. Los ministros del diablo: El trabajo y sus representaciones en las minas de Potosí. IRD, IFEA and French Embassy in Bolivia, 2005.

Absi, Pascale and Pablo Cruz. “Patrimonio, ideología y sociedad: Miradas desde Bolivia y Potosí.” Tinkazos 19 (2005): 77-96.

Bakewell, Peter. A History of Latin America to 1825. 3rd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Castro Varela, María do Mar and Alisha M. B. Heinemann. “Mitleid, Paternalismus, Solidarität.“ In Geflüchtete und Kulturelle Bildung: Formate und Konzepte für ein neues Praxisfeld, edited by Maren Ziese and Caroline Gritschke. Transcript, 2016.

Cruz, Pablo and Pascale Absi. “Cerros ardientes y huayras calladas: Potosí antes y durante el contacto.” In Mina y metalurgia en los Andes del Sur desde la época prehispánica hasta el siglo XVII, edited by Pablo Cruz and Jean Joinville Vacher. IRD and IFEA, 2008.

Flores, Yuri. “En el Cerro Rico todavía operan 32 cooperativas mineras.” La Razón, April 22, 2024, https://hemeroteca.larazon.bo/economia-y-empresa/2024/04/22/en-el-cerro-rico-todavia-operan-32-cooperativas-mineras/. Accessed August 1, 2025.

Francescone, Kirsten and Vladimir Díaz. “Cooperativas mineras: Entre socios, patrones y peones.” Petropress 30 (2013): 32-41.

Gnecco, Cristóbal. “El señuelo patrimonial: Pensamientos post-arqueológicos en el camino de los incas.” Diálogos en Patrimonio 2 (2019): 13-48.

Lane, Kris. Potosí: The Silver City that Changed the World. University of California Press, 2019.

Macusaya Cruz, Carlos. En Bolivia no hay racismo, indios de mierda: Apuntes sobre un problema negado. Jichha and Nina Katari, 2020.

Pretes, Michael. “Touring Mines and Mining Tourists.” Annals of Tourism Research 29, no. 2 (2002): 439-456, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00041-X.

Quintana C., Ernesto. “El legendario Cerro Rico de Potosí: Historia, recurso, símbolo.” In Anuario 1998, edited by Archivo y Biblioteca Nacionales de Bolivia. Archivo y Biblioteca Nacionales de Bolivia, 1998.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolo-nizadores. Retazos and Tinta Limón, 2010.

Schacht, Lars-Michael. “Ethnografie des Minentourismus in Potosí, Bolivien: Eine kritische Diskussion.“ Unpublished bachelor’s thesis, University of Bonn, 2024.

Smith, Laurajane. Emotional Heritage: Visitor Engagement at Museums and Heritage Sites. Routledge, 2021.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg. University of Illinois Press, 1988.

UNESCO. “City of Potosí (Plurinational State of Bolivia) added to List of World Heritage in Danger.” Last modified June 17, 2014, at 19:00. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1148/. Accessed August 1, 2025.

UNESCO. “City of Potosí.” Accessed October 8, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/420/.

Vergopoulos, Hécate. “Breaking and entering, or a feeling of heterotopia in tourism situations.” Via 9 (2016), https://journals.openedition.org/viatourism/393.

Xie, Philip Feifan. “Introduction: The Scope of Industrial Heritage Tourism.” In Industrial Heritage Tourism, edited by Philip Feifan Xie. Channel View Publications, 2015.

Lars-Michael Schacht, graduated in Latin American Studies from the University of Bonn with an ethnographic work on mining tourism in Potosi, Bolivia, is currently studying for a master’s degree in Anthropology of the Americas at the same university. For more than five years he has been working at the BASA museum, the archaeological and ethnographic collection of the Department of Anthropology of the Americas at the University of Bonn. He has gained practical experience at the Bolivian National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore as well as in the research projects “Scientific Collections on the Move” and “Heritage and Territoriality.”